Rendering the Essence

December 23, 2014

David Levine is best known as a caricaturist, but, as a recent exhibition of his work at Forum Gallery demonstrates (“The World He Saw,” December 11- January 17, 2015), he was a masterful painter as well. When, due to macular degeneration, he could no longer create the finely-lined caricatures for which he was renowned, he continued his life-long exploration of the human form and the language of paint.

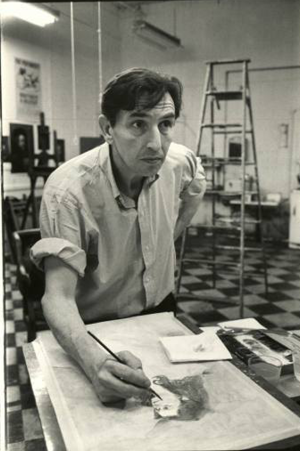

Levine demonstrates how he once drew

In November 2008, a little more than a year before he died, C-SPAN interviewed the great American artist David Levine. We see Levine in the environment he inhabited for decades: the floral-papered walls of his Brooklyn Heights apartment; the messy shelves bulging with books; the desk where he sat to draw the caricatures for which he became famous; the long, narrow hallway populated with favorites of his own pictures. The interviewer asks him the usual things, about how he got started with The New York Review of Books and the insight that led him to draw Lyndon B. Johnson pointing at a Vietnam-shaped scar on his abdomen and Henry Kissinger screwing the globe—images that are commonly thought to be among the greatest caricatures of all time, both for their mastery of craft and sharpness of commentary.

Halfway through the forty-five minute interview, with Levine sitting at his heavy wood desk, the interviewer asks, “You work in pen and ink?”

“In pencil first,” Levine says. “Like Michelangelo did.”

He holds a pen and demonstrates how he executes his caricatures—or did before macular degeneration made it hard for him to complete a detailed drawing. He brushes a dry quill across the paper, authority in every gesture, even though he was not drawing anything, just remembering.

“And I understand that you’re not doing those drawings anymore, that you’re having trouble with your eyes?” the interviewer asks.

Levine says he’s having “terrific” problems, that one of his eyes is “dead” and the other “about fifty percent useful.” “I see things generally,” he says, “but I only see the larger cavities of form. I don’t see the color of your eyes, I don’t see a lot of things that I really used to see much more clearly. So I’m finding it very difficult. I’m trying various things. Mostly I’m trying pencil.”

“So you’re not doing political drawings anymore?” the interviewer asks.

“Not anymore.”

Painting his beloved Coney Island

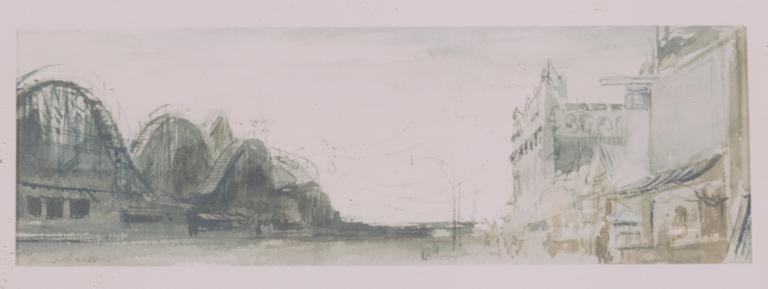

Levine explains that he is focusing solely on painting now, returning, as he has so often, to his beloved Coney Island, trying to get at “the tumult that takes place in the water.”

As the C-SPAN camera pans over a painting on an easel, Levine talks about how “oil painting is from life.” He says he wants to “touch the internal feelings of people.” He says enjoyment is at the heart of art-making, or should be. The painting on his easel, now entitled The Last Battle, will be among his final ones. Due to his declining health, it was never finished. We can nonetheless glimpse in it some of the aspects of craft that made Levine an artist of historic magnitude, as profound with paints as with pen and paper, if not more so.

Levine’s early life

Born in Brooklyn in 1926, Levine had a prodigious gift for drawing and painting that seemed to define his life. Indeed, his trajectory is so single-minded from such an early age, his talent so remarkable, that his artistic development reads mythic. In many ways it was.

Levine’s parents worked long hours, his father as a small garment shop owner and his mother as a nurse and political activist. This meant that he was frequently alone. His activity of choice during his solitary hours was drawing. Such was his skill that he was invited to try out as an animator at Walt Disney Studios when he entered a contest at the age of 8 or 9. He drew his way through P.S. 241 and Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. And when he was drafted to serve in the armored infantry in 1944, he drew his way through that experience, as well, making maps in Egypt and contributing cartoon illustrations to Stars and Stripes. Discharged from the military in 1945, he chose to study at the Tyler School of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Initially, he intended to get a teaching certificate. Instead, he gained a solid foundation in painting.

At Tyler, Levine also made two lifelong friends, the portrait painter Aaron Shikler and the gallery owner Leroy “Roy” Davis. As Davis explains, the three men “had a common love of painting and shared an admiration for some of the same painters. We were all generous with one another. They were supportive of me when I was struggling to make my mark, and I was supportive of them. We just hit it off; we were friends.” The three of them moved to Brooklyn shortly after graduating with the goal of becoming painters.

Building a career as a caricaturist

Drawing was a foundational skill for Levine, as it was for many great painters. He used it to test out compositional strategies, to gain a deeper understanding of light and shadow, to quickly record what he saw, to refine the form and figure of a subject. But in Levine’s work drawing is elevated beyond its workmanlike function to become a tool of both seeing and communicating subtle, complex truths about our visual and emotional world.

At the heart of his great skill as a draftsman was his uncanny ability to boil things down to a few defining elements—that’s the nature of caricature, finding what distinguishes a person and exaggerating it. This gift shone through from an early age.

He carried a sketchbook, in whose pages he recorded the people he encountered during his days—fellow straphangers, workers, neighbors, friends, teachers, street people. You cannot enter the home of one of his many friends without being shown sketches Levine did and left for others to gather, like fallen petals, on napkins, the backs of bills, tiny sheets of paper torn from his sketchbooks. These treasured drawings, many done in less than a minute, include his depiction of Hans Hoffmann’s gigantic, grinning, bulbous-nosed head presiding over a ship of minions, a broom instead of paintbrush in hand. (Levine briefly studied with Hoffman and this caricature shows him and Shikler jumping ship.) The painter Lennart Anderson still laughs when he remembers a sketch of Levine’s he saw in the 1950s, tacked to the bathroom wall in Leroy Davis’s gallery, of an art critic whizzing through an exhibit on roller skates.

By Levine’s early adulthood, newspaper and magazine editors had come to recognize and reward his gifts as a caricaturist. His caricatures consequently became a primary source of income throughout his life. And thus began a professional trajectory apart from his painting.

Caricature was a job Levine loved, but painting was his passion

Levine’s gift as a draftsman came to international attention when he began publishing his caricatures for the The New York Review of Books. His drawings of prominent literary, artistic, and political figures graced every issue from 1963 until 2007, when he was essentially fired because macular degeneration had changed his drawings. By then, he had become known and appreciated by a vast number of people, many of whom were unaware that drawing caricatures was Levine’s day job—a job he valued and loved and took pleasure in—but painting was his passion, and perhaps even greater gift.

As he ascended to fame as a caricaturist, he continued painting, sometimes in oil, more frequently in watercolor after the 1968 loss of several large paintings in a devastating studio fire.

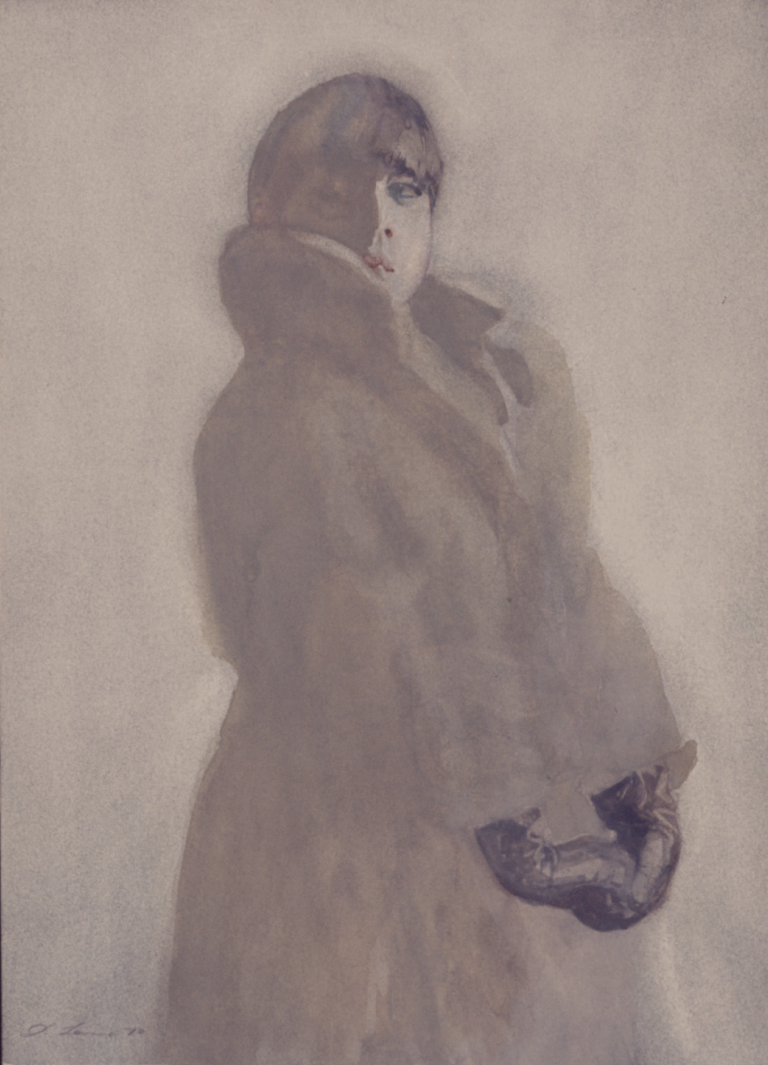

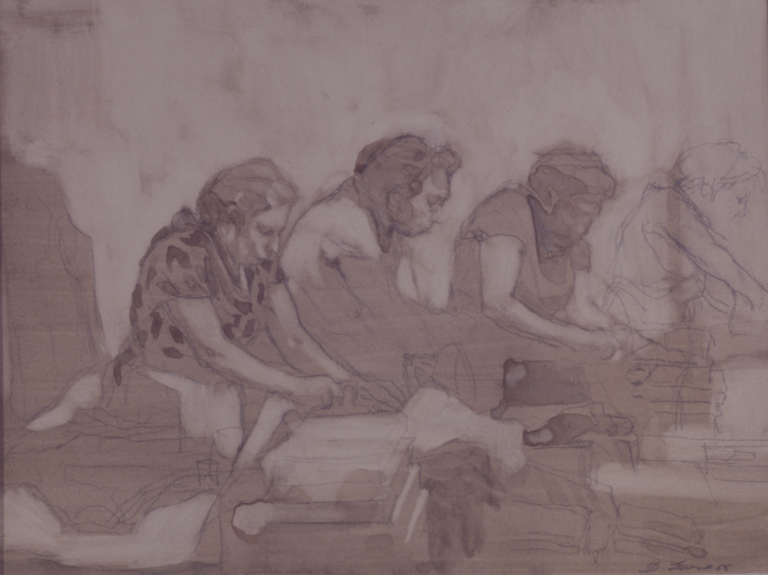

His paintings are of bathers at Coney Island; tired models posing in the evening at the art school Levine and Shikler founded in 1958; garment workers at his father’s shop; friends and family members. They’re of the Coney Island roller coaster on the verge of majestic ruin, and the expanse of concrete as wide and lonely as possibility in front of the subway station at the end of the line, where New York City empties into the sea. His Coney Island scenes depict bathers entwined, their bodies nearly fused, water and heat seeming to meld otherwise separate beings into a calligraphic sequence of shared humanity. Outside of Coney Island his people are more often solitary—and shimmering. They simultaneously emerge from and disappear into light, impossible to fully grasp, their faces only partially revealed, their selfhood ephemeral yet inarguably intact.

If in his caricatures Levine’s vision is often deeply, unequivocally critical of human greed and the will to power, in his paintings he shows empathy and an appreciation for what cannot be expressed overtly about his fellow man.

The mastery Levine’s last paintings reveal

Though lacking a certain detail and crispness of line that we expect of his work, Levine’s The Last Battle, partially because it is unfinished, reveals some of what makes Levine’s paintings so deeply compelling. At the foundation of even his most complex paintings was a masterful design sensibility, laid bare in The Last Battle, based on interlocking shapes of shadow and light, as well as a visionary insight into the subjects he took on.

Through an alchemy that was all his own, Levine created a harmonious visual whole by mere suggestion—the “larger cavities of form” that he refers to in the C-SPAN interview, and that were clearly evident in his earlier work, such as The Operator painted in 1965. In The Operator, the large masses he blocked in, the architecture of dark and light, the abstract puzzle of negative and positive shapes, create a visual experience in which there are no parts and pieces but something altogether unified, the bedrock of his artistic vision and the foundation of all great painting.

“An Embroider”

This powerful design sensibility, which Levine suggests he had to rely on entirely as his vision deteriorated, had formed the vital inner scaffolding of all the paintings—and perhaps the drawings—he did throughout his life.

Painted only six years before The Last Battle, An Embroiderer (2003), included in the Forum Gallery exhibition, exemplifies these same principles. Masses of color bleed into each other, balanced, though in An Embroider enjoying further refinements of line and detail. Levine mentions Michelangelo in his C-SPAN interview, and we see homage to this giant in the muscular shoulder girdle of the workingwoman. Surely Levine must have equally admired and studied the great painter of light, Vermeer, with these droplets of pigment becoming light itself, a pearl necklace floating over a field of pale violet shadow.

As with so many of Levine’s watercolors, on close examination An Embroiderer shows a complex dialogue between the artist and the medium. We sense that the formal languages of shape and line were awake and alive while he worked, pools of watery color soaking into the paper as he drew his brush from one shape into another. Pigment once suspended, loose and swimming on the damp paper, dries and fixes itself, surrendering to Levine’s perseverance and insights.

In the end, his central work

Comparing the qualitative aspects of Levine’s work to that of Michelangelo, Vermeer, Tiepolo, or even Francisco Goya, court painter to the Spanish Crown who pioneered the sensibilities of caricature in his Los Caprichos etchings, it is curious that Levine’s paintings are not better known. Unlike Goya, who was known foremost as a painter and whose caricature emerged from his painting, Levine’s work as a caricaturist seemed to have overshadowed his painting. Perhaps this is not all together bad. Perhaps the commercial success of his caricature was the very shield that protected the tender insight of his watercolors, for who can say whether the sensitivity and nuance that we see in his work would have survived had he been painting with an eye toward commercial success.

While a source of suffering for him, Levine’s forced retirement from The New York Review of Books allowed him to spend more time near the end of his life with his central work. And, as he could no longer see or depict the particulars that he’d said in the past were necessary to get to “the general that’s believable,” he instead turned to a general that hearkens toward the particular experience of being human we all share.

Comments

A remarkably good description of a great man, a great american, a great artist.

Thank you so much for sending this to me.

Thank you, Barbara. It was an honor researching and writing about David.

I am thrilled that you take us into the artists, “products” and “process”.. and deal with the loss of sight so skillfully without sentimentality. You have done us ALL a favor I think. Please continue!

Softness of fabric born into the place of milky shadows. I suspect his fathers work was not only subject, but also a kinetic tie

Leave a Comment